Story:

We were an Urdu-Punjabi speaking family living in Quetta. My father, Mohammad Hussain, originally from Hoshiarpur, Punjab, was a contractor for the railways. I was born to my mother, Sakina Bibi, in 1932 and given the nickname ‘Bala.’ The great earthquake of 1935 was so destructive that it forced our family to move back to our ancestral village, Jaida, in Nawanshahr District, Hoshiarpur, Punjab.

In Hoshiarpur, I enjoyed quite a playful childhood, and I especially remember my best friend Hameeda whom I miss even today. We played on a swing that we made ourselves, and played pittu garam (seven stones). There was a school for boys in Jalda where my brothers studied. All the teachers were Sikhs. There was no school for girls in our area.

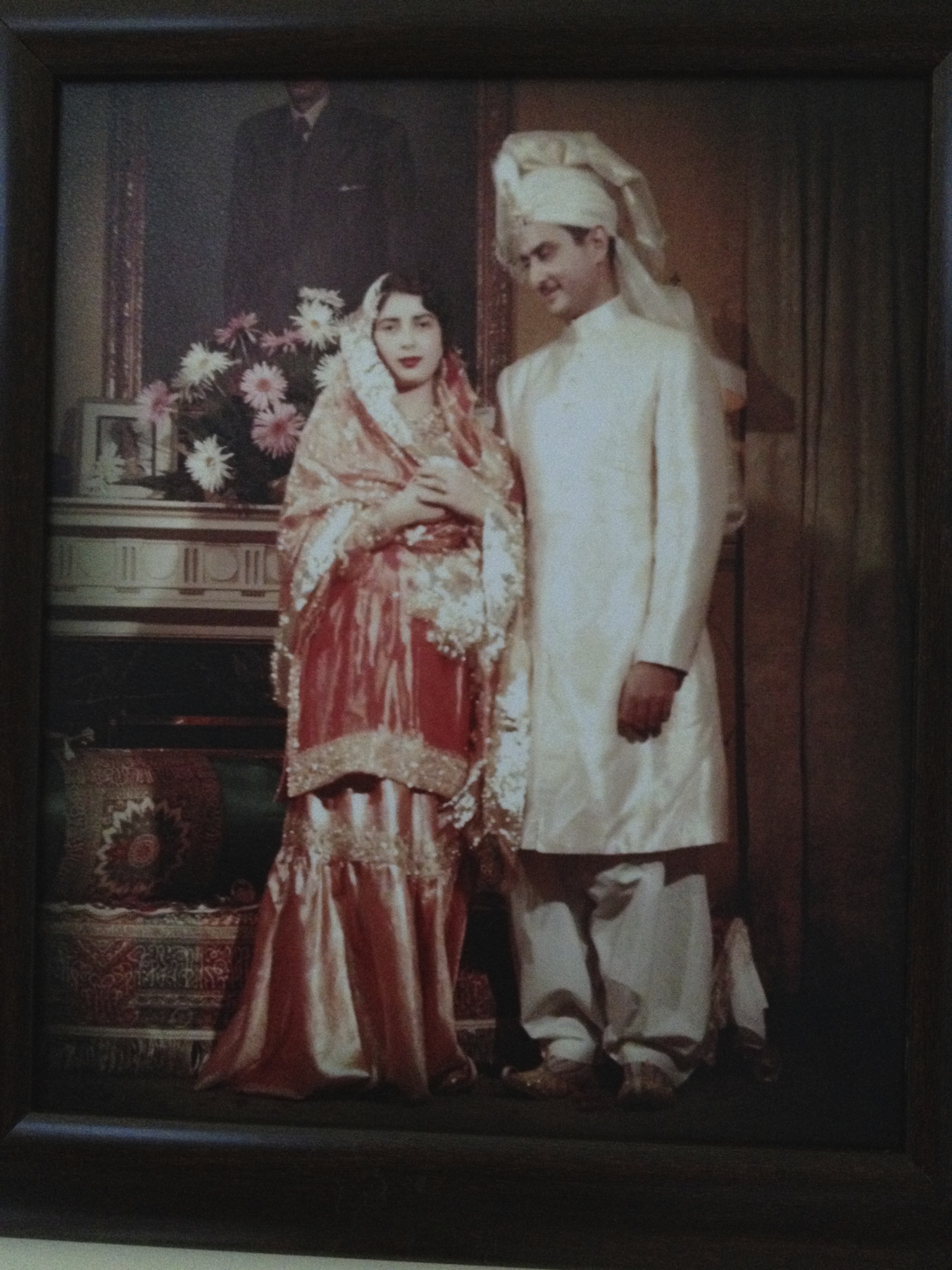

The monsoon was celebrated with zeal. Young men and boys would play the dhol (hand drum with two heads) and put up dance performances. In 1945, I was married to one of my elder cousins who lived in Boothgarh, Garhshankar District, Hoshiarpur (now in Ludhiana District). I was 13 and he was 23. I continued to live at my parents’ house because, as per the tradition of our village, there is a maturity period for women before we are ready to leave with our husbands. I moved in with him in my 20s.

Relations between Sikhs and Muslims in the village were cordial. Only after Partition did everything turn upside down. We were very lucky. The Sikh families in the neighbouring village were very caring towards us and alerted us that insurgents were planning to attack our village at 2:00 am.

My parents, my siblings and I packed up our belongings and began our journey on foot and bullock carts. It was the second day of Eid. After travelling two miles, we reached Mehndipur village in Mukerian district. At that point, we learned that our village was under attack and there was no turning back for us. The glimmer of hope that things might settle down and that we might return home was gone completely. From Mehndipur, we went to my husband’s house in Garhshankar. We were surrounded by Sikh families there. They were my husband’s, and they vowed to travel with us to ensure our safety.

The first journey, to Chankoi, Nawanshahr, was 12 days long. The Sikh families accompanied us for the first 11 miles to make a statement that they were our kin. At Chankoi, about 500 to 600 migrants (25 families) gathered for the journey to Lahore. We moved towards the bank of the river Sutlej and made camp for the night. We walked for 10 miles and crossed the river in the morning towards the spot where my sister’s in-laws’ house was located. We stayed there for 15-20 days. From there, we went on to the Rahon camp at Shaheed Bhagat Singh Nagar district, where we stayed for over two weeks, and then moved on to Behram, Banga tehsil at Nawanshahr district where another refugee camp for migrants was set up. We stayed there for another 20 days.

Throughout the journey, we stayed away from villages as much as possible. We were moving along the shores of the Sutlej River with the rest of the caravans that were ahead of us. We saw mutilated bodies floating in the river. The scale of bloodshed and violence spread to the river too.

I met many female survivors of violence at the Chankoi, Rahon and Behram camps where we stayed for over two months during our long journey to Lahore. There was a woman who was stranded. Her people was murdered and she pierced herself with pins to the point of bleeding profusely. She hid among the other dead bodies. She escaped on her own after the insurgents did their bidding and left.

I saw a man sitting in a tree. He became insane and kept asking the way to the river so that he may drown himself to death. The man was father to seven daughters and seven sons. All his sons were slaughtered in front of his eyes and all his daughters were missing. He would not come down from the tree.

I feared for my honour and my life. I camouflaged myself in mud and filth so that I may appear ugly or unnoticeable to the insurgents who were specifically abducting and raping good looking women from the camps.

People from my husband’s village were dying of diarrhoea and cholera during our journey. They were drinking water from the wells and eating whatever they found easily accessible. There were no doctors in any of the camps to treat them. Our condition worsened at the Behram camp. About 100 or 200 people died of the water-borne diseases by the time we reached Behram. My mother-in-law was one of them.

We were picked up by the military from Behram and taken to the Amritsar Railway station on a fully loaded truck. The journey from Behram to Lahore took 15 long days. At the Amritsar Railway Station, our truck was attacked by insurgents. Luckily, we were in the hands of the military, and the soldiers managed to curb the situation without causing any bloodshed. We took the train to Lahore and entered the city via the Wagah border, reaching Lahore a day before Eid ul Azha. People were preparing for celebrations. We had seen too much human slaughter and bloodshed in this long, painful and dangerous journey, and now Eid ul Azha was upon us in Lahore.

From Wagah border, we moved to the refugee camp set up at Walton Cantonment. Jinnah came to visit us there in a bus. He met everyone at the camp, said some nice things, and then left. We stayed at the camp for a night and then moved to a house near the Lahore Railway Station that my brother managed to acquire for us, using our father’s work affiliation with the Railways. We stayed there for six months until the new Pakistani government allotted our family six acres of land in Dunyapur, in the district of Multan, in exchange for our property in Nawanshahr, Hoshiarpur, which was now in India. We moved to Multan and then Lyallpur (now Faisalabad) for 12 years.

I have four sons and three daughters, and I live with my sons, daughter-in-laws and grandchildren. One needs strength and courage to do the right thing, and one has to work towards achieving that strength. Otherwise we suffer the consequences of making wrong choices for the rest of our lives.