Name: Subash Khanchand Bijlani

Interviewed By: Ishika Chatterjee

Interview Date:

Interview Location:

Story:

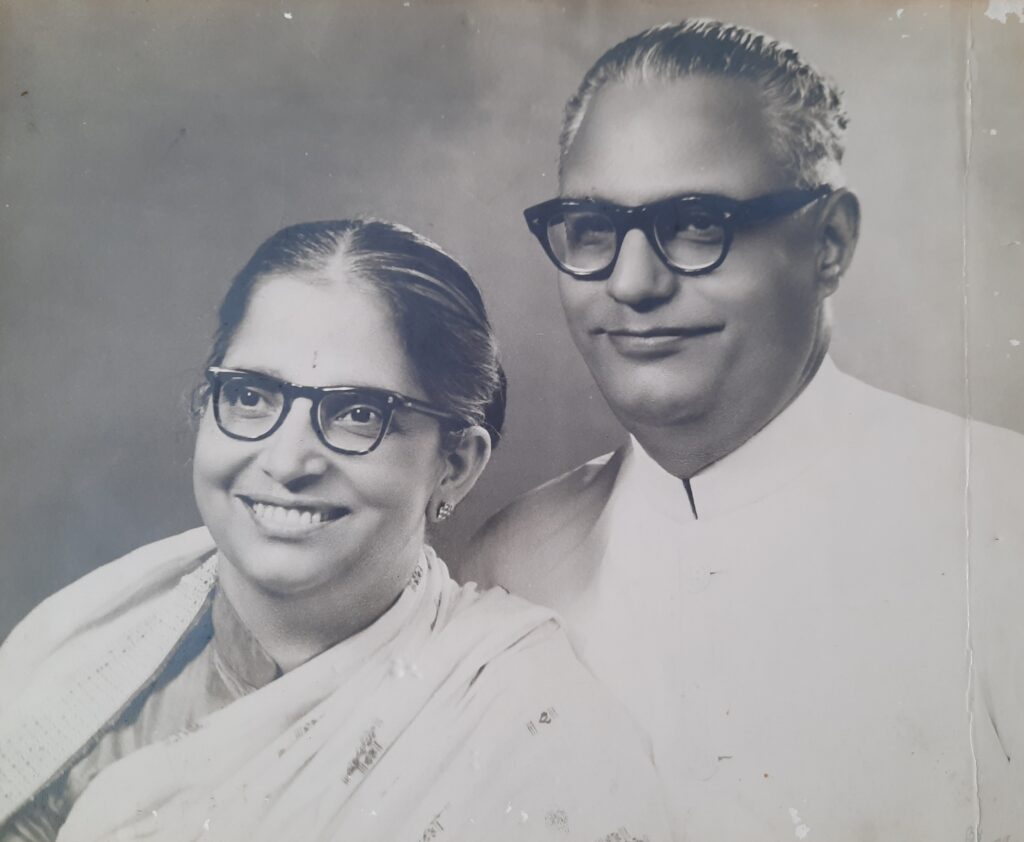

I was born in 1942 in Thatta, Sindh. My parents, Khanchand Bijlani and Jassie Motwani were born in Manjhand and Larkana in Sindh respectively. My paternal family had traditionally worked as tax collectors in Sindh. In the mid-1970s, we had a family tree prepared which traced our roots in Sindh as far back as 1655. My maternal family, the Motwanis, were well-known in Larkana. The Motwanis’ business, named Chicago Radio, involved the import of broadcasting equipment to India. During British rule, they operated an underground broadcasting system as part of the freedom struggle and supplied equipment to Congress. My mother once saw Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose in person, at a Congress meeting, at my grandfather’s house when she was young. Netaji had a great impact on her, so much so that she named me ‘Subash,’ in his honour.

We moved from Thatta to Hyderabad to Quetta, and eventually to Sukkur, Sindh, where I spent most of my early childhood, and where my father was a reputed judge. Our family was a nuclear one. I had three sisters at the time, and three other siblings were born after Partition. The court where my father worked was a massive structure, on a hilltop. It was locally known as the Vadhi Takri (Big Hill). A small dirt road led to the judge’s house where we resided, at a place called Nandhi Takri (Small Hill). The families of all staff employed at the court resided close to the Nandhi Takri. This constituted the neighbourhood since our house was otherwise quite isolated, and we had no other neighbours in Sukkur. I remember playing with the children of the Court’s employees. The families and staff were mostly Muslim. There was no religious animosity between Hindus and Muslims in the neighbourhood. We were particularly close to one of our domestic staff, Jhamman Singh, and his family.

Of my days in Sukkur, I remember sleeping under an open sky and gazing at stars at night. I also remember riding a tonga (horse driven carriage) around town. At home and in school, the only language I spoke was Sindhi. English was not a household language in Sindh – it was distinctly the language of the courts, the administration, and higher education. I learned Hindi after Partition and learned English during my higher education. I no longer dream in Sindhi. The festivals I remember being celebrated in Sindh include Jhulelal, Janmashtami, Guru Nanak Jayanti, and Thadri (festival specific to Sindh), during which only raw, cold food could be eaten. I remember the poetry of Shah Abdul Latif, the Sindhi Sufi mystic and poet, and the Sindhi wedding songs, known as Lada. I was fond of Sindhi dishes such as kadhi made of besan and vegetables, sai bhaji (Sindhi vegetarian curry), and lola (Lolo or Sindhi Sweet Loli is one of the most famous Sindhi festival food, made from wholewheat flour, jaggery, sugar and ghee), which was traditionally eaten during Janmashtami. The food was highly influenced by the proximity of the Indus River, and as a consequence, fish-based dishes such as pallo (Sindhi fish dish) were popular too. Even today, I cook Sindhi delicacies such as koki (a dough filled with onions and coriander), dal pakwans (Sindhi breakfast), lotus stems, and sanna pakoras (fritters) at my home in the United States.

By August 1947, news of disturbances had approached Sukkur. There was no mass exodus out of Sindh yet nor was there any overt violence. My father and his colleagues were determined to remain in Sindh. My first and most distinct memory of Partition is of 14 August 1947, when the British flag was lowered from atop our house, and the Pakistani flag hoisted. I accompanied Jhamman Singh and two constables to hoist the new flag. Meanwhile, refugees began to arrive in Sindh in large numbers. This eventually sparked conflict in Sukkur, and my father was advised by his colleagues that our family must leave before the violence worsened. In January of 1948, my family, along with the family of Jhamman Singh, went from Sukkur to Rohri station by tonga. At Rohri, we boarded a train for Rajasthan. The train would be stopped at all stations, and several people would storm through the compartments. Owing to my father’s connections, our compartment was guarded by Muslim constables. Years later, Jhamman Singh recounted to me that the policemen had saved his life in the train, by placing him in handcuffs, and lying to the mobs that he was a prisoner who had to be transported. From Rajasthan, we moved to Bombay (now Mumbai) where my mother’s family owned some property. My father managed to get a government job as a Fact-Finding Officer, in charge of investigating claims of property lost by refugees due to Partition. However, the position was soon dissolved, and we had to relocate several times before finally settling in Calcutta (now Kolkata). Coincidentally, our new home was on the same street where Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose had once resided.

An important family heirloom, a traditional jhula (swing) that had been constructed in Thatta in 1942, to commemorate my birth, is still with us. Jhulas or ‘peengas’ are of great cultural significance for Sindhi families. When our family moved from Rohri to Rajasthan by train during Partition, we left with very few belongings. However, the one thing we made sure to carry across the border was the jhula. To this day, I am unsure how we managed to make that long, arduous journey with the dismantled swing. It was a massive structure, supported by two frames, and made out of heavy, expensive Burmese Teak. Today, the jhula is not only the most important heirloom of our family, but it is also a memento of our pre-Partition roots in Sindh. It is the only structure from Sindh that still remains with us. There is a great sense of rootlessness and alienation that permeates the displaced Sindhi community in India. This might be best encapsulated by Munnawar Rana’s poem ‘Muhajir.’