Story:

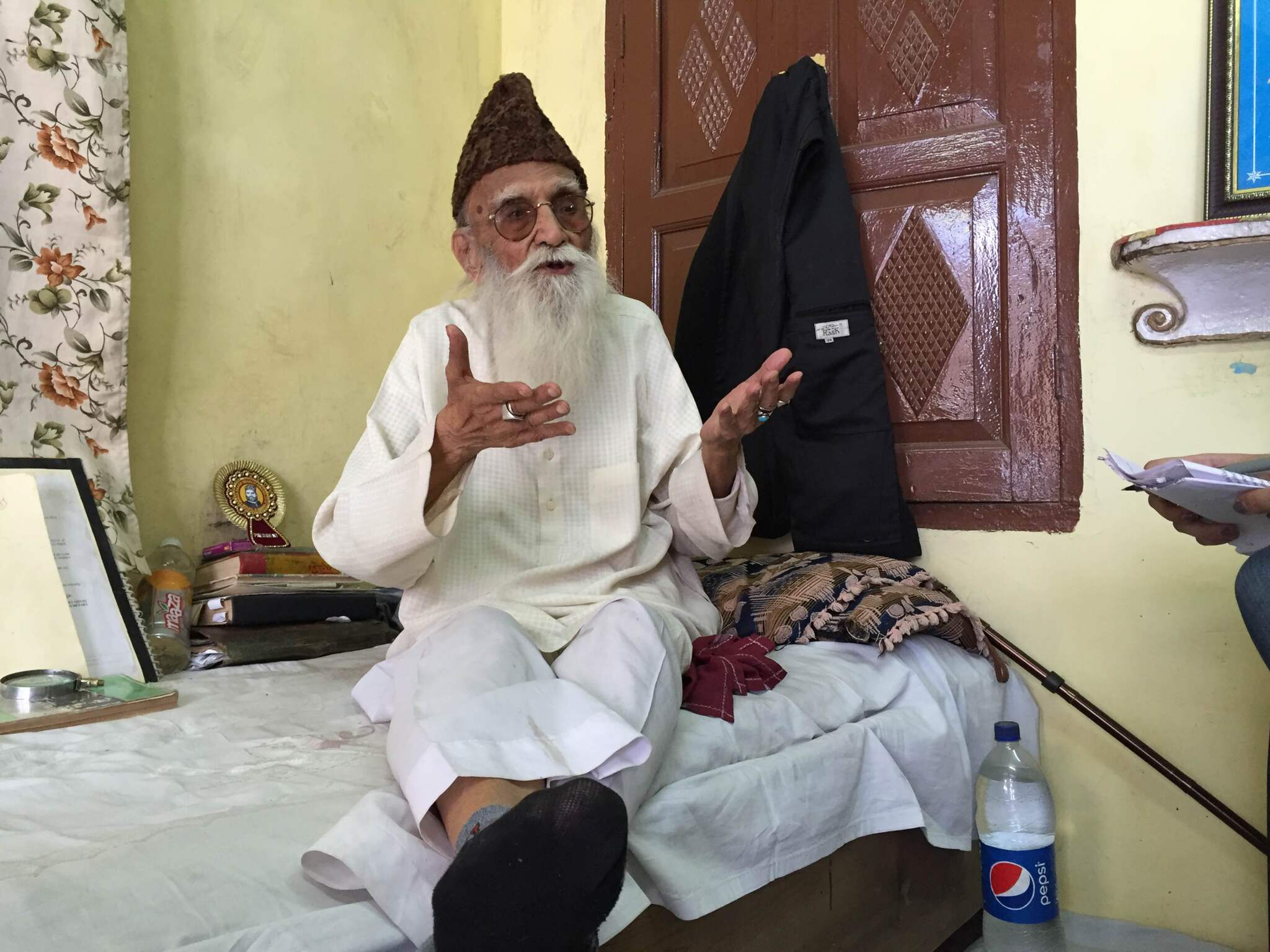

I was born in 1933, in the village Dhudial, then in District Jhelum, (about 80 kilometres from the modern city of Islamabad), with a 5% Sikh population. Former Indian Prime Ministers, Dr. Manmohan Singh and Mr. Inder Kumar Gujral, were also from the same district. My father’s name was Sardar Balwant Singh and my mother was Sardarni Ram Piari. My father was a businessman and my mother was a housewife. I had one brother and one sister, who were younger than me. As kids, we rode bicycles for miles for fun as most sports in our village were traditional, like kabaddi. Bicycles were also the best mode of transportation for us. I used to travel to different villages using horses or bicycles, but primarily travelled to my mother’s village. We lived in a normal three room house, which was common for our village, with an open courtyard where we kept our buffalo. My mother always milked the buffalo, and made milk products at home. In our area, there were no hospitals close by, but there were midwives and some local clinics.

People from my village were there for a hundred years or more; Muslims migrated to this village eventually too, but due to the rule of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the Sikh population had gained many benefits and prospered with large land holdings. My uncle, Bhagat Singh, was one of the best athletes in the area at that time and was often invited to display his skills at sporting events.

People from the Sikh community were money lenders, which I think was a good profession for them. Land was minimally used for farming as the area was hilly and most land holdings were still used to grow wheat, some vegetables, and flowers. Most women in our village worked on the charkha (loom). They bought cotton from East and South Punjab, to make khadi (handspun cloth). Muslims worked as farmers and artisans, while the Sikh community was entirely business based. The two communities did, however, share the same passion for the army.

In those days in our village, the most popular music was kirtan at the gurdwara (Sikh place of worship), and folk songs. For entertainment, people played volleyball and cards when they had enough time to do so. Some other forms of entertainment were shopping where people from Kashmir and Peshawar came to sell hing (asafoetida spice) and other rare commodities. Most festivals were celebrated separately by the communities and mostly in religious sites. The education in my village was great and we had a majority of Sikh educators and some Muslim teachers.

I remember hearing about the Akali movement led by leaders like Master Tara Singh. The meetings would take place in our village gurdwara. The people of the village were interested in freedom from the British but not necessarily in the idea of Partition. They hadn’t anticipated it.

When the time came for people to migrate in 1947, they assumed that eventually there would be peace and only took a few things with them as they thought they’d be able to go back. When we migrated we only had clothes, no money or other possessions. We took the train to India from the railway station in the village. The train took almost 10 hours for us to get from Rawalpindi to Patiala, which was travelling onwards to Delhi. We stayed in a gurdwara for many months; there were about 120 other people living in small rooms there. During the trip, we closed all the train windows so that we couldn’t see outside and no one could peek in. This was also a tactic to avoid being attacked. The atmosphere was tense in the train, as everyone was stressed.

I think that Partition should have been peaceful, but the leaders didn’t allow it. Many other nations had situations like ours, but avoided the blood shed that we saw – at least half a million lost lives. It’s hard to imagine how neighbours living next to each other became enemies. We became like animals. I saw people being killed, houses being burned, bodies of the people flowing in the canals and people being shot in trains. I saw this happen everywhere in Punjab, and it was a horrible scene. I saw ladies weeping and men being killed on the streets of Patiala. One can’t imagine how a human can be so wild. Something like this can be avoided worldwide if the authorities strictly follow principles and rules.

Once we moved to Patiala, I was a child labourer and didn’t attend school for a year. I collected eggs from different villages and sold them to people. A while later I continued my schooling from all the scholarships I received for being an outstanding student. My father started a business there but couldn’t succeed. Soon after we all moved to Patiala and I finished my studies. Upon moving to Patiala, we were allotted a house based on the possessions we had left behind. We felt that the compensation wasn’t completely fair, but it was helpful.

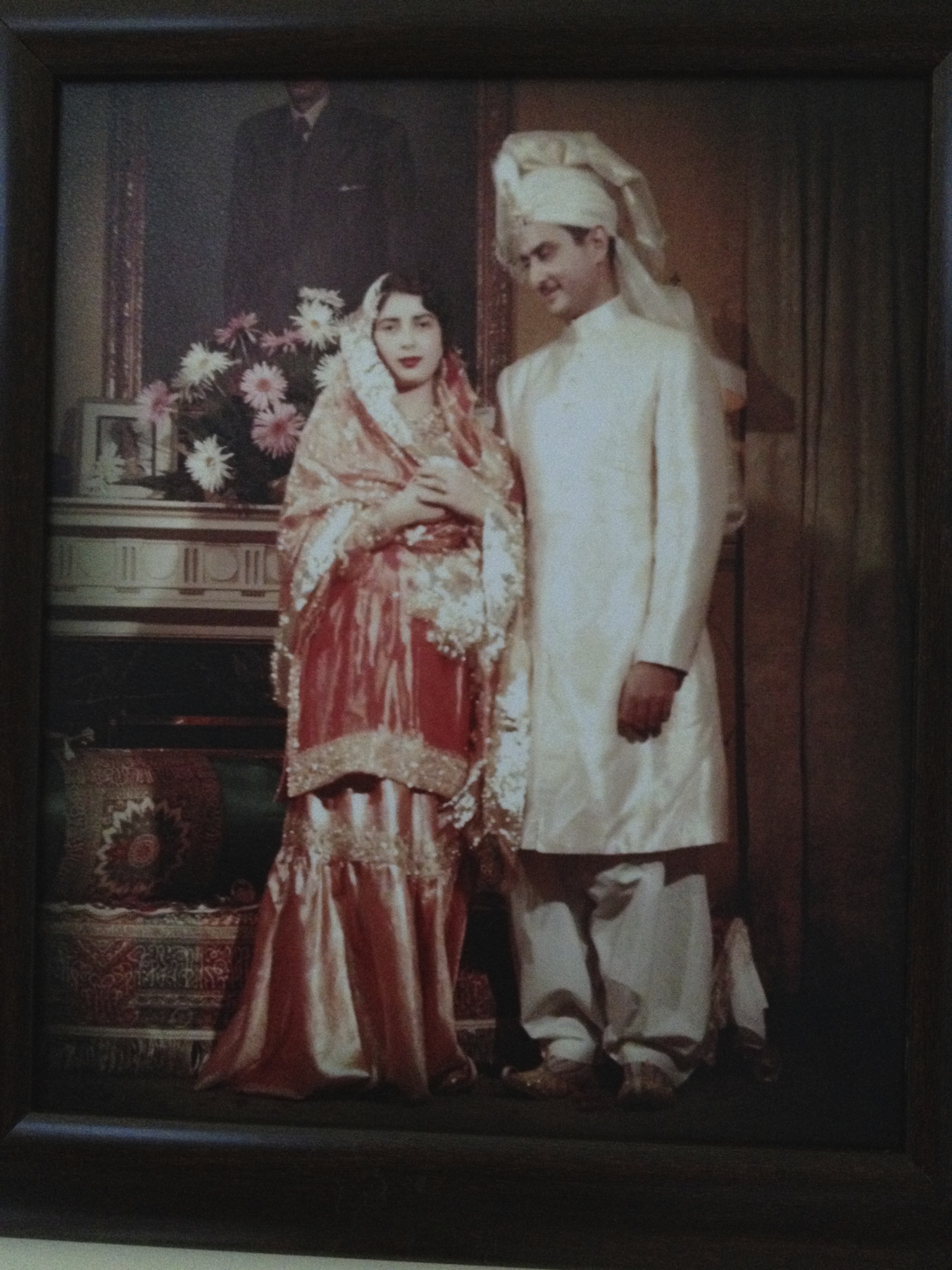

Once I was done with schooling, I managed to make a living and got involved in tourism. I joined service in Punjab and joined the public relations departments. I got married in 1951. I met my wife when I was posted in Public Relations in Bhakra Dam. Our parents agreed and then we got married.

I then worked in Rashtrapati Bhavan in Delhi. I feel I’m a success story: a refugee with such a poor start, and with no money, who ended up making it! I headed the Department of Tourism in Delhi for seven years, and then served as a Member of Parliament for five years, and finally was the first Sikh person to become the Chair of the National Commission for Minorities. I also worked to help the agricultural sector grow.

I remember my visit to my village, where I lived before migration; it wasn’t the same, not as prosperous and not as lively.